Quest to the Kwai

The Irish Times July 12 1986

These days the death railway, as the Allied prisoners of war gruesomely called it, has a new lease of life. You can take the small diesel train from Thonburi station in Bangkok. It travels right up to the end of the line, where it peters out in a patch of nondescript jungle at Nam Tok, three hundred kilometres northwest of the Thai capital and near the closed border with Burma.

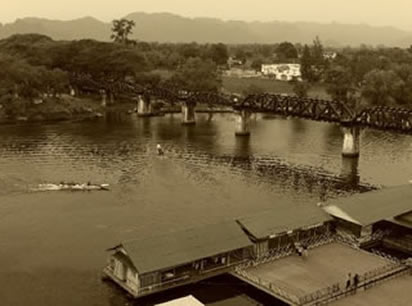

On the way you pass the infamous River Kwai, at probably the most well known bridge in history, cinema history at least. Even though the Hollywood movie was shot on location in Sri Lanka, then Ceylon, people continue to think of the reconstructed version in the western Thai jungle as living up to screen reality.

The four-carriage railcar I boarded left on the dot of eight, with the Thai national anthem blaring from the station’s PA speakers, as every morning, and the few well wishers and vendors on the platform were standing to attention. The fish markets to our left were in full swing. Octopus, lobster, live crab trussed in bamboo leaf, garupa, varieties of cockles and mussels, and an assortment of eels. They’d all been transported up-river from the Gulf of Siam that morning. Compared to them I was looking the worse for wear, with a hangover and an hour’s cross-city taxi ride behind me, and still no sign of breakfast.

Opposite my seat a vendor of something or other meticulously and with an addict’s delight prepared her betel juice wad. Every alf hour of the three-hour journey she spat a long stream of crimson out the carriage window. Her lower lip looked like a strawberry well past its prime, or Dracula on an overdose. Sometime during the journey she got off at a tiny village in the middle of nowhere.

The train has its sprinkling of ‘budget travellers’, talking hostels and getting wired up to portable sound, strictly Lonely Planet types. Budget traveller gives the whole business an air of respectability. When I was their age we called it ‘doing the world on the cheap’.

There were Sunday trippers from Bangkok, swinging down the aisle in search of seats. Well-dressed, middle-class city-dwellers sporting fake Louis Vuitton bags and thermos flasks, off to visit relatives and country cousins or to show their kids what real Thai life was like before rollerdiscos. There’s only one class on the Bangkok-Kanchanaburi-Nam Tok train, third, which solves everything.

Rural Thai life took over as soon as the shanty towns of Bangkok had gone by. The best way to see real Thai living is to board a train – any train – out of Bangkok, and to hang out the window or, as was the case here, the wide-open doors. It was the middle of the rainy season (May-September) and the vegetation was newly lush and all the coffee coloure streams and rivers gushing. There were spits of rain but the downpour held off and the indigo clouds lumbered South to the Malayan peninsula.

The train stopped at each station and we were inundated with kids selling everything from grilled banana to spiced chicken legs. You could buy plastic bags of coffee, hot or iced. The kids ran up and down the aisles with their wares perched precariously above or on their heads. I had some Thai doughnuts and unscrewed my thermos of coffee like everybody else. People were busy outside hauling water from a well, using the lever pump method. Yellow robed monks reclined on their terraces after their morning meal, the only one of the day and donated by villagers for merit in the early hours.

Kanchanaburi was the first big town. It’s a crossing point for the twin streams of the River Kwai. Cars have to ford by ferry. At the station exit there were the usual touts proffering guesthouse cards as we alighted. It was a short walk from the station to the centre of town, but you can hire a trishaw, a sort of bicycle coupled with a baby carriage. Most of the drivers are very poor and their life expectancy is short, due to heart failure.

On the way into town I stopped at the Allied war cemetery, which on Sunday is a place for a picnic for city-dwellers. There was an air of festivity, common in Thailand. A ghetto-blaster beat out cover versions of sentimental hits over the food stalls and the neat rows of war dead.

There are a number of World War II cemeteries in the area but this one was the largest. Most of those buried there were under 25. Almost all had died helping to build the railway I had just travelled up on: one for every 800 yards of track.

Malaria, the appalling conditions in the camps, lack of medicines and exhaustion from over-work accounted for many more. I came across an epitaph in Irish, of all languages, and paused a while remembering how long it was since I had heard it uttered.

I headed for the relative quiet of the JEATH Museum, in the grounds of a riverside monastery or wat. On the way I had an English/Irish breakfast (which for some reason Thai people think is American!) at a bakery I’d discovered on a previous visit. The ex-cook of the Iranian ambassador runs it, and she calls me ‘master’ as she brings in the bacon and eggs. It’s a delightful place and she makes the best lemon meringue pie this side of the iron curtain, topped with chocolate chip ice cream.

The JEATH Museum (Japanese, English, American, Thai something or other) is a collection of sepia photographs looking the worse for post-war monsoons, and tattered canvases housed in one of the original POW huts. A monk handed me a sticker on entering and a Coke on leaving. In the visitors’ book, Japanese, English and American tourists jostled for suitable comment: ‘forgive but not forget’; ‘they tortured but we bombed’.

In the confines of the wat some boys had arranged an ant wrestling championship and I wandered over to join the audience. The ants were given a touch of toothpaste for adhesiveness and put in the ring. Cowards were cajoled; the heroes fought it out to the bitter end. The wat boys (who act as messengers and servants for the monks, in return for some schooling) found it all a source of amusement and distraction in the hot afternoon. It seemed a funny reductio ad absurdum, there where so many had died.

I hired a trishaw out along the back roads to the bridge. There are restaurants where you can wait for the train to cross while tucking into some splendid freshwater fish.

The river was clogged with slow-moving weed, the kind they used for camouflage in the film The Bridge Over the River Kwai. There were kids fishing with punctured aluminium basins, like gold prospectors, while busloads milled about taking photographs.

I met a shy Amerasian novice monk, fourteen and with beautiful hazel eyes and freckles. He was the butt of the wat boys’ jokes. They made a pretence of telling me he was from Laos but obviously he was the child of American GI presence in the area during the Vietnam War. Quite often such children are sent to monasteries to keep them out of harm’s way.

There’s a TAT (Tourism Authority of Thailand) office in Kanchanaburi, offering raft accommodation on the river, long-tailed boat trips, guided tours of the surrounding jungle, Khmer ruins and waterfalls.

On a previous trip I’d stayed with the train to NamTok, which means waterfall. A minibus from the River Kwai Village Hotel came to collect us from the group of huts around the end of the line. It was a splendid air-conditioned hotel with garden and swimming pool, tucked away by the river, miles from the nearest village.

There were perched eagles, owls and monkeys in the foyer to welcome us and we were treated to videos of Alec Guinness sweating it out in the stoic manner and to The Deer Hunter, which was filmed just downstream. The film crew had used the hotel as a base and the staff weren’t going to let us forget it. Trekking tours were on offer and the many stunning waterfalls were accessible by motor launch.

There were only three guests there, so we had a pool party and took rowing boats out on the river, highly recommended if you want to get away from it all. Watch out for leeches, crocodiles and the odd iguana.

There are air-conditioned buses every hour back to Bangkok. On the video they were showing M*A*S*H, the volume up at maximum. The sky hogged the last of the light – crimson and saffron tints – and I read until it got dark.